Have you ever noticed your dog straining to pee or having accidents in the house? While these signs might seem like a simple UTI, they could actually point to something more serious — bladder stones. These hard mineral formations can cause discomfort, infections, and even dangerous blockages if left untreated, making them something you definitely don’t want to mess with.

Bladder stones are surprisingly common in dogs, especially in certain breeds, and understanding the signs, causes, and treatment options can help make your dog’s bathroom breaks less stressful and painful.

What Are Bladder Stones in Dogs?

Bladder stones, also known as urolithiasis or cystolithiasis, are hard, solid mineral deposits that can develop within a dog’s bladder. These deposits begin as very small crystals that eventually combine with one another, fully hardening and forming stones. Dogs that have urinary tract infections are more likely to experience the hardening and combining of these crystals due to the bacteria in their bladder providing ideal conditions for growth.

There are two primary types of bladder stones in dogs: struvite and oxalate. These two types of bladder stones make up a majority of all canine uroliths.

Struvite Bladder Stones in Dogs

Struvite crystals within the bladder are made up of magnesium, ammonium, and phosphate. While the presence of these components in a dog’s urine is not always a cause for concern, they can help create a perfect environment for stone formation when combined with specific bacteria, such as Staphylococci and Proteus bacteria.

These bacteria produce an enzyme called urease, which turns urea into ammonium. This ammonium, along with the infection and inflammation present in the bladder, forms a sticky matrix that traps struvite crystals, creating a stone. Struvite stones develop in alkaline urine, and in dogs, they almost always result from an infection. Simply put: no infection, no struvite stones.

Research has shown that struvite bladder stones more commonly affect females than males, with approximately 85% of patients with struvite stones being female. This difference in prevalence based on gender is due to a female dog’s higher susceptibility to bladder stones due to their anatomy and hormone levels. Female dogs have a shorter and wider urethra than male dogs do, making it easier for bacteria to enter the urethra and eventually move to the bladder, causing infections like UTIs.

Like female dogs, some breeds are also genetically more prone to developing struvite bladder stones due to genetic, anatomical, and metabolic factors. Miniature Schnauzers, Shih Tzus, Cocker Spaniels, and Yorkshire Terriers are all predisposed to developing recurrent bladder infections and UTIs due to their bladder anatomy and the alkaline pH of their urine. Other breeds like Labrador Retrievers and Dachshunds are at risk for the development of struvite bladder stones when eating diets high in minerals or with low water intake. Across all breeds, struvite bladder stones are most common in younger dogs, with the average age of bladder stone diagnosis being 2.9 years.

Oxalate Bladder Stones in Dogs

Calcium oxalate bladder stones, more commonly referred to as simply oxalate bladder stones, are the second most common type of bladder stones in dogs, second only to the struvite stones we just discussed.

Unfortunately, the formation of oxalate bladder stones in dogs is not as well understood as struvite stone development. Current research suggests that diet and certain concentrations in urine play a role in the development of oxalate crystals. Dogs that have acidic urine high in calcium, citrates, or oxalates create an environment that is favorable for the development of these stones. Acidic urine can result from diets that are high in protein and rich in acidifying ingredients, like methionine. Additional research into the formation of oxalate bladder stones in dogs indicates that diets high in carbohydrates and low in phosphorus may also contribute to stone development.

Oxalate bladder stones are most common in male dogs, with males representing approximately 73% of oxalate stone cases. Like struvite bladder stones, some dog breeds are predisposed to develop oxalate bladder stones. Miniature Schnauzers, Lhasa Apso, Shih Tzus, Bichon Frise, and English Bulldogs have traits that make them more likely to develop oxalate stones at some point in their life.

Common Symptoms of Bladder Stones in Dogs

The primary symptoms of bladder stones in dogs are related to urination – with many symptoms being similar to those associated with a UTI – and are often the first symptoms that pet owners will notice. Bladder stones may also affect a dog’s energy and appetite levels due to pain or discomfort, causing even more secondary health issues, like unintentional weight loss.

Bladder stones in dogs can cause a range of symptoms, depending on their size, number, and location, but a few of the common signs include:

- Frequent urination

- Straining to urinate or general difficulty urinating

- Blood in the urine

- Painful urination with vocalizing or visible discomfort when urinating

- Accidents in the house due to urgency or incomplete emptying of the bladder

- Licking the genital area excessively

- Cloudy or foul-smelling urine

- Reduced urine flow or dribbling urine

- Lethargy or decreased appetite (if infection or obstruction occurs)

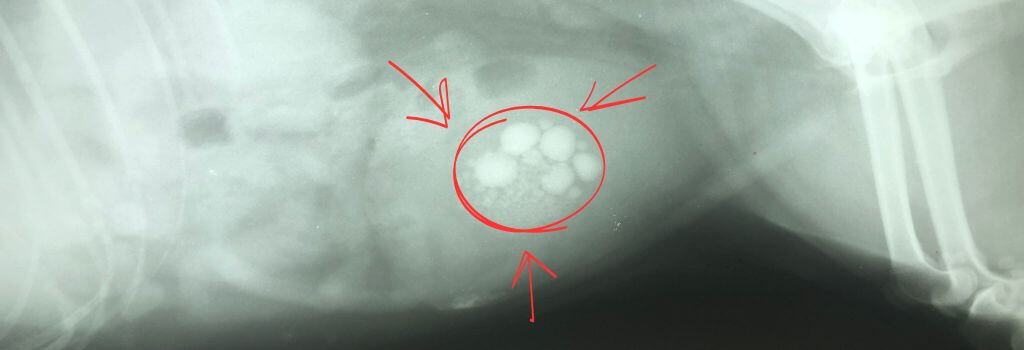

However, symptoms are not always present to tip off owners that something is wrong. Some dogs may exhibit only minor symptoms or, in some cases, no symptoms at all, making detection of bladder stones more challenging. In some instances, bladder stones are even found by mistake, with veterinarians detecting their presence when investigating other health issues with X-rays or other imaging techniques.

Diagnosing & Treating Dog Bladder Stones

Diagnosis

There are a number of ways that veterinarians will be able to detect bladder stones in your dog. Typically, a veterinarian will begin with a physical examination of your dog, specifically looking for any notable symptoms, including abdominal pain, fever, or unintentional weight loss. In some small breeds, veterinarians may even be able to feel the presence of bladder stones in dogs when physically examining a dog.

Following a physical exam, if a veterinarian suspects the presence of bladder stones, the following tests may be performed to confirm the diagnosis:

- Urinalysis

- Bloodwork

- Ultrasound

- X-ray

Treatment & Removal

Treatment and removal of bladder stones in dogs will depend on which type of stone you’re dealing with. With struvite bladder stones, there is a wider variety of options ranging from surgery to dietary changes. Your veterinarian will assess the number and size of the stones, as well as your dog’s overall health status, to recommend an appropriate treatment or strategy for stone removal.

Struvite bladder stones in dogs are most commonly treated and removed through:

- Dissolution with Diet – Prescription urinary diets like Hill’s c/d or Royal Canin Urinary SO can work to dissolve struvite stones by acidifying the urine and reducing magnesium, ammonium, and phosphate levels that are typically responsible for stone development. However, it’s important to know that dietary changes are only effective if there is no major build up of stones or urethral obstruction.

- Surgical Removal – For dogs who have many stones or very large bladder stones that can not be passed on their own, surgical intervention is usually required. A veterinarian will perform a cystotomy, where they will surgically open the bladder and flush out the urethra to remove the stones.

- Antibiotic Therapy – Since struvite stones are caused by urinary tract infections, antibiotics can be used to eliminate the infection while the stones dissolve.

- Voiding Urohydropropulsion – For small stones, a catheter and saline flush may help expel them from the bladder.

- Laser Lithotripsy – In this minimally invasive procedure, a laser is used to break stones into smaller pieces so they can be passed in urine. While effective, lithotripsy is only available at some specialty hospitals and few veterinary practices that have the required equipment, so be sure to check with your veterinarian to see if it is offered in your area.

Options for dissolving or removing oxalate bladder stones are a little more limited, as existing stones are unaffected by dietary changes and antibiotics. For oxalate stones, veterinarians most commonly recommend either surgical removal or urohydropropulsion. The technique used will depend on the size and amount of stones, as some stones are too large to be flushed with urohydropropulsion and will require surgical removal.

Preventing Bladder Stones in Dogs

Working to prevent the formation of bladder stones can go a long way in keeping your dog healthy and comfortable. There are a number of things pet owners can do at home to prioritize their dog’s bladder health and lessen the chance of stone development, even in predisposed breeds.

If your dog struggles with bladder stones, try:

- Increasing their hydration

- Feeding them a prescription diet to eliminate factors that contribute to stone development (Talk with your veterinarian about best options for your pet and be sure to hold onto your prescription card to order food!)

- Monitoring their urine health and pH levels

- Preventing and treating UTIs as soon as symptoms begin

- Keeping up with your dog’s annual wellness exams to give your veterinarian a chance to catch bladder stones before they cause major problems

Don't have a vet in your area yet? We can help you find a local veterinarian.

If you have more questions, the GeniusVets Teletriage platform will give you unlimited access to text and/or video calls with board-certified veterinarians! To learn more click here.